Socelect.org

The first fully functional version of socelect.org is now published, up and running.

It uses an algorithm invented by Andrew Davenport in the early oughts (about fifteen years ago) to aggregate multiple preferences into a ranking that accurately represents the preferences of the majority. To quote the site, “Find alternatives that satisfy most.”

The series that follows is a personal story about the development of socelect.

What is preference aggregation?

The following will help with some of the jargon necessarily used here.

-

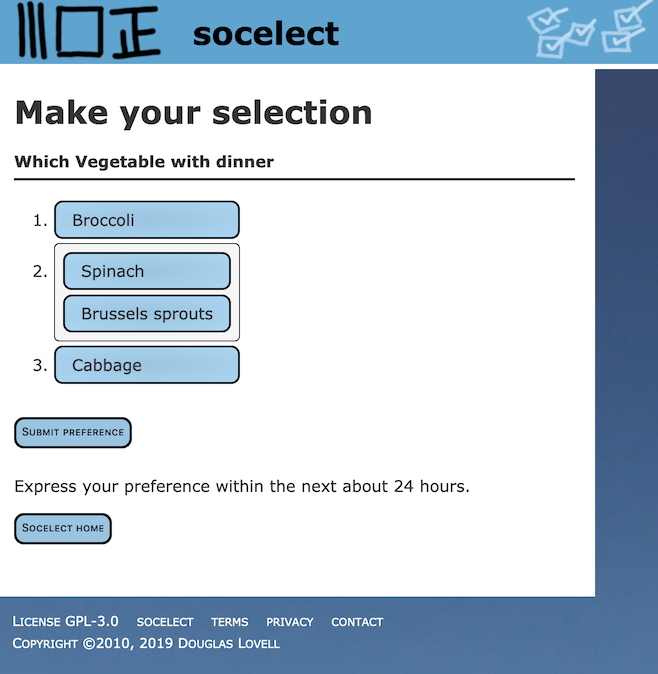

partial order is just an ordering of things, one before the other, in which some things are equal. This is opposed to a full order in which everything comes before or after every other. You can say “broccoli before spinach before brussels sprouts before cabbage.” That is a full ordering. You can say “broccoli before spinach and brussels sprouts, and after those cabbage.” That is a partial ordering because, while you prefer broccoli to spinach and brussels sprouts, you don’t prefer either of spinach or brussels sprouts before the other. You do prefer both over cabbage.

-

preference aggregation is taking some number of individual preferences for broccoli, brussels sprouts, spinach and cabbage, and putting them together to decide which to serve as a vegetable with dinner. (Steak and potatoes all the way for the rest, and chocolate cake for desert.) Although you’re choosing one vegetable to serve, everyone knows that their second choice is as meaningful as the first, particularly if they don’t want to eat cabbage.

In another scenario you might be choosing top three, or ranking everything. The Davenport algorithm provides a partial order ranking for all of the alternatives.

When attempting to measure group preference given more than two alternatives, it is well established that asking each person to choose one, and then selecting that which gains more votes than the others (plurality), is likely to result in a selection that the majority of the group dislikes. There are many alternative systems that are better. I believe that preference aggregation is the best.

Having each individual rank the alternatives gives full information about which alternatives they prefer over others (although it doesn’t tell how much). With that, we can truly select alternatives that satisfy the most.

The parts

To make it happen required these projects:

- A user interface for specifying partial orders.

- An implementation of the Davenport algorithm.

- The web site built around a database system.

Language choice

It made most sense to implement the Davenport algorithm in the C language because the C language has great compilers that make it very fast for most computers, and it needs to be very fast. Others might have chosen C++. Never did like it.

For the web site I resisted going with Elixir and Phoenix, which are new and shiny and very interesting. I also easily resisted Node.js because, well, JavaScript. PHP frameworks likewise aren’t my cup of tea or coffee. The framework I chose is Ruby on Rails. I know it well, it works well, and it still suits me. Also, Ruby plays well with C because it is itself implemented with C.

The decision to use Ruby over Node.js (JavaScript) or Elixir is in reality a big decision. Node.js and Elixir carry a very important distinction over Ruby. They have in their core an asynchronous model of execution. They enable programming hundreds or magnitudes more individual tasks in a Cirque de Soleil juggling ballet. Ruby plugs along doing one thing until it’s done. The deeper reality of these statements is a topic for another day. They don’t at all tell the real or full story.

The combination of C and Ruby meant one more project:

- A Ruby extension library to use the C implementation of the Davenport algorithm with the Ruby code of the web site.

Priorities

Some of the projects have dependencies on others. The web site depends upon the user interface. The Ruby extension depends on the Davenport implementation. After that, I had two criteria:

- interest and motivation

- risk mitigation

It makes sense to do the riskiest parts first, because failing these all of the other work is for naught. To me the implementation of the Davenport algorithm was the riskiest. It’s complex, and the C language can punish little mistakes with hard to solve problems.

Second after that was the user interface. User interfaces have to seem simple and it takes a lot of work to get them that way. Further, it needs to be in JavaScript because that is the programming language for web browsers. JavaScript is still a bit wild, with lots of changes to the language and the tooling around it. Some of that tooling helps with the uneven implementation of features of the language within the browsers.

For motivation, someone laid down the gauntlet by saying that I didn’t have the technical mettle to get a handle on JavaScript. Sometimes it doesn’t take much more than that– a good project and being slighted.

Up next

The posts that follow track development of the four projects. Hopefully, they will contain insights about how to develop software, what it’s like, and lessons learned. They will chronicle a journey, some of the choices, important crossroads, mistakes, and difficult passages.

Ride along with me a spell. Let’s see what we’ll discover. Meantime, try out socelect.org. Let me know what you think!