Ashes of Truth

A couple of months ago, I listened to a pod-cast from Hi Phi Nation about a disagreement between the documentary film maker Errol Morris and philosopher Thomas Kuhn. The podcast is called, “The Ashes of Truth” Season 1, Episode 9, 18 April, 2017.

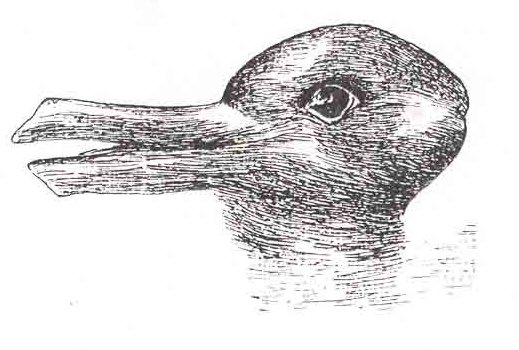

According to the pod-cast, Thomas Kuhn, in his popular book of 1962, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions described and gave name to the phenomenon we call “paradigm shift.” He used it for scientific breakthroughs; but, we’ve generalized the meaning. In the paradigm shift, a system of belief is shaken by some new observation, a new fact that is undeniable but impossible to integrate into the system. The system of belief has to change.

There’s the phenomenon that we only see and seek out that which reinforces our beliefs, discounting, avoiding, denying, even attacking anything uncomfortable that might be incommensurate with our beliefs. (There’s the phenomenon too that social media machine learning algorithms are very good at learning and reinforcing that behavior in their drive to survive, reproduce, and grow.)

The paradigm problem

When we watch or listen to a documentary, more than when we watch or listen to the news, we have an expectation of being presented with facts and truths. But truth is filtered through perception, our perception and that of the film maker. Perception is influenced by our knowledge, values, education, upbringing, in fact our belief system or working paradigm about how the world functions.

From this you can say that a film about the murder of a police officer, “The Thin Blue Line” isn’t factual or documentary at all, but just another story. The people in the film are relating what they saw or heard filtered through their perceptions and beliefs. The film-maker is deciding what to record based upon their belief. The editing, sequencing, and presentation of the film recordings that make-up the movie are all intentional, filtered through what the makers of the film have come to believe and want to present through the film. If you don’t like where it goes, you use that to discredit it.

“The Thin Blue Line” presents a case study about how we can become enamored with a story that’s congruent with our beliefs, blinded to facts. Another, longer one, is “The Hurricane Tapes”, a podcast about the prosecution of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter for a triple murder.

There’s more to both, such as when accepting a fact or correcting a wrong would mean betrayal of your clan. In the Hurricane story, not giving anything away, two clans are at war, and the truth serves neither.

Conspiracy theories

How is it that a person can believe that the moon landing of 1969 was faked in a studio? Lots of people believe this. How? Never mind that thousands of people were involved with the moon program, hundreds would have to be involved in a studio production of such magnitude, and that the President of the United States would have to have been part of the act. Never mind that all of those people would have to consistently maintain the fiction. Said President was later found to have attempted cover-up of a different scheme of much smaller scale and equal import.

It must be that, to the faked moon landing believers, the picture of a film studio is familiar and possible. They can imagine it. Imagining three people two hundred fifty thousand miles away in two metal cans powered by rockets, for real, talking to other people on earth using electromagnetic waves, sending pictures from the moon. That’s just too much. Impossible.

To believe the second, that two people were on the moon and a third orbiting the moon above them, you have to be comfortable with a world of technology of which you have no understanding, that there’s a world of engineering capability around you, that you walk in day to day, that you’ll possibly never grasp, with any amount of effort, in your lifetime. You have to accept that your life and knowledge and place in the world is limited, perhaps smaller that you’ve ever imagined before. And then integrate that into a sense of self that you can live with.

Nature of knowledge

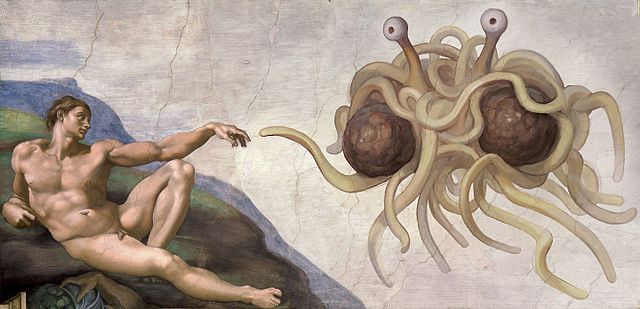

When called to believe in something we don’t understand, how do we distinguish between the flying spaghetti monster and landing on the moon? One is something we have to take on faith, for whatever purpose, to feel as if we have understanding. The other something we can learn about and understand, rather than deny as something that can only be accepted on faith. Thus the importance of education in creating a world where self-serving reductionist arguments about relative truth and the truth of your lies don’t get you to a position of high political office. Did I make too big a leap there?

We hate not knowing. Our nature is that we are extremely uncomfortable with lack of knowledge. We’ll often go to great lengths to present any amount of explanation of something we know nothing about simply to avoid a simple admission that we just don’t know. This extends so far as to cause us to believe in our explanations and, beyond admitting it, not even to be aware that we just don’t know. Instead, we accept the stories constructed by or for us, anything plausible, rather than remain in the uncomfortable vacuum, the inhospitable, virtiginous free-fall acceptance of nothing, no knowledge. No idea.

The face of things

We all have stories. In a way, having stories is how we’re visible. We tell our stories and layer privacy.

You have a story about yourself that is public, more stories for friends, more stories for intimates. In the outer sphere, you create a persona that people will accept and if you’re ambitious, you manipulate it. It’s safer to tell a story than to have others make one up for you, although they’ll do that too.

We’ve entered into a world in which people who manipulate truth and perception have unprecedented power to do so. From a position of notoriety and attention, with an intuitive or well educated, practiced understanding of the nature of seduction and belief, you can command support to put you in a place of real power over real things. (It’s probably been that way for a long time. Only now we have Twitter.)

In order to be immune to fictions, in order to be real, we can’t simply be attentive to facts, actions, what is directly observed. We have to accept that without them, we just don’t know. Uncomfortable as that is, a story feels so much better, it’s very likely the case. Without facts, we have to live in the space of no idea, nothing, no assumptions. When it comes to measuring the motivations of a human being we’re especially in the dark, as Robbie Burns penned: “What’s done we partly may compute,// But know not what’s resisted.”

There is truth

Errol Morris notes in the pod-cast that, “Everything is a reenactment. Consciousness is a reenactment of the world outside of our skulls, and the task is how to get back to the world from that reenactment inside of our skulls.”

You don’t have to load-up a documentary film with a regressive, recursive journey through all of the filters of perception and interpretation until it becomes a work of art, fiction, a story invented by the people who made it. No. It’s a documentary film, made broadly or narrowly within the conventions of documentary film. It isn’t a Star Wars movie. It isn’t a Jason Bourne, James Bond, or Indiana Jones thriller. It isn’t “The Silence of the Lambs”. It’s a telling of something that really happened, however much you don’t like it.

There is truth. It’s complicated. However, that you ordered the prosecutor to ignore your friend’s involvement in a crime is a fact. You did or you didn’t. You didn’t say it but not mean it, expecting the prosecutor to ignore you. You didn’t wink as if to say, “Yes, I’m saying that for my friend, but go ahead anyway.” The prosecutor didn’t misinterpret you. Any of that is revisionary denial to give your supporters a way to keep supporting you, and another lie in the stack you’ve built your house on.

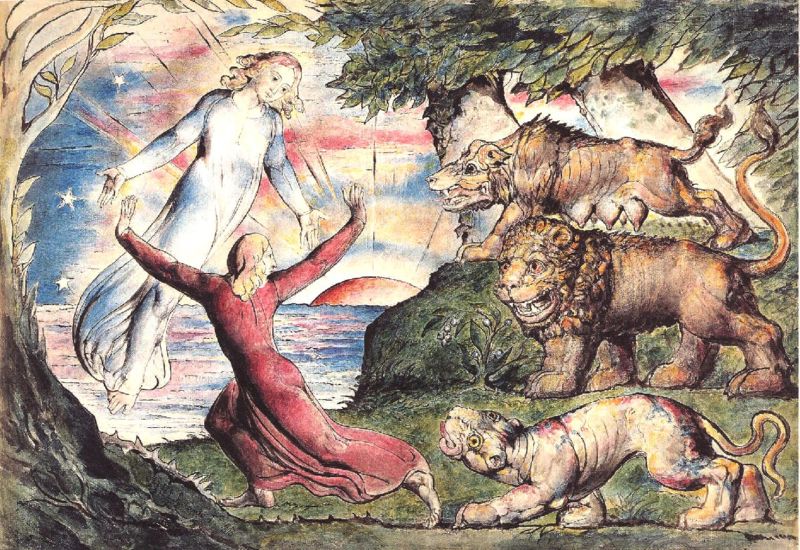

Comfort with the abyss

A friend, the same friend who shared the pod-cast with me, shared an essay by Timothy Kreider, Life Is What Happens In-Between. It talks about the feeling we have when our lives are disrupted by travel or unexpected major life changes. It describes the uncomfortable feeling of disconnection, having been unplugged from our routines where suddenly we question who we are. It describes a sense of dislocation and “being in the world”, and how these periods of dislocation can get us out of our own heads, into a virtiginous sense of possibility, direct experience, and perspective.

The best art somehow makes us feel that discomfort. Just enough. Not too much.

For me, it is seeing that we swim in an ocean of lies, and I’m one of the fish. When I think I’m being honest, I’m lying to myself. When I reach for authenticity, I often miss out on a true thing.

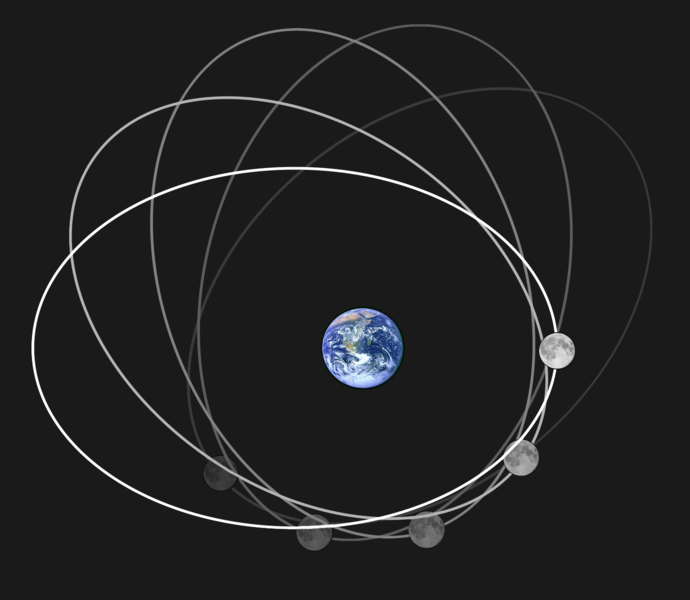

Eventually we settle down and we’re still the same person. The unsettling shift to a new way of thinking becomes just a fact, like, that the plane of orbit of the moon is about five degrees away from the ecliptic and twenty-eight and a half degrees away from the equator. Understanding why the moon wanders around so much in the sky, rising and setting in different places, is one more aspect of the world integrated into the whole of what is us. It becomes an expansion of the experience. Life goes on. We’re wiser. Until the next time.