Caught Between Borders

Back in December I gave up my apartment, retired, and began four months of nomadic life. Traveling in Uruguay, enjoying the beaches in southern hemisphere summer, I began to make plans. I’ve always wanted to try living on a sailboat and sailing the free and open waters of the world. I’ve been preparing through study and learning to sail. It’s time to pull up roots and find my new home aboard.

La Paz, Baja California Sur

On the Baja peninsula of Mexico there’s a little tourist town called La Paz. There are a lot of sailboats there, a community of fellow U.S. ex-patriot sailors, and wonderful anchorages, I’m told, among the coastal islands of the Sea of Cortéz. After a short visit at the end of February and return to Montevideo to keep a promise to a friend, I’m back in La Paz, in the middle of March, doing the pre-purchase inspections and sea trial for a new sailing home.

But what am I doing here? It feels like, almost while I’ve been sleeping, the world has disappeared. The tourists running to catch boat tours and swim with the whale sharks in February are completely absent now in March, which is high season. The beautiful pedestrian walk along the beach, the Malecón, that hosted the parades of Carnaval is sprinkled with a few locals out for walks or jogs. A few whale boats sit idle. Restaurants are closing. I’m the only guest in the hotel. Everyone is talking about Corona virus. Virus virus virus is all I hear. Everywhere virus.

The human race has become a race of hermits hiding in their homes, working and chatting on the internet. The consensus is that it’s necessary to do this to save our species. I had better get with the program and find a place to do the same. Only I don’t have a home. The boat isn’t right. It’s a no go.

Somehow being in a poor town in Mexico whose source of income has evaporated and economy has collapsed doesn’t feel like the best option. It’s one thing for those who live there; but, maybe a bad idea for a visitor.

Caught out

I’ve heard that the U.S. border has closed to all, even citizens. In the few days I’ve been checking-out the boat, the airline that carried me from Uruguay has suspended flights. Uruguay has closed borders to all but citizens. I’m not certain that my residency-applied-for status will allow me entry, even if I book the four leg journey on multiple airlines to get there. This is too strange!

A friend in Lisbon, Portugal has invited me multiple times to visit with him there. He has invited me again to stay in an apartment with a view that he owns in a nice part of town. He assures me that with a place to stay, invitation from a friend, and promise to quarantine for two weeks I’ll be admitted. He has verified this with someone who knows.

Lisbon to me is a place apart, of legend, like the lost city of Atlantis. That I know someone who lives there is itself a thing of magic to me. Lisbon launched a thousand ships in the age of exploration, European expansion, colonization and conquest. Lisbon, where thousands of refugees escaped from Europe to America in WWII. Portugal! A legendary nation of sailors and fishermen! Could it someday launch me on my own explorations?

After my quarantine my friend and I can return to musings about philosophy, politics, government, society, film, literature, and women over wonderful meals, coffee, drinks and beers there in his home town. What better hide-out could I find while the world stands still?

The travel agent in La Paz is sweet. I can get to Mexico city via Aero Mexico where British Airways will carry me to Lisbon via London. It doesn’t cost a fortune and I’m booked for the flight in the morning. They warn me that there are a lot of cancellations. I’ll take my chances. Life, really living, is a series of small or larger risks with random rewards. I’ve been hooked on that for a while, so off I’ll go. Lisbon is the next adventure.

FAQ

-

Are you crazy? Have you heard there’s a deadly virus going around? A. I’m not afraid of getting the virus. According to the data, a person of my age with no medical problems has a 99.4% chance of survival. I might be uncomfortable, but I’m not going to die.

-

Have you noticed? We’re all sheltering in place to slow down the spread of the virus? A. While I’m not afraid of getting sick, I am afraid of spreading. I’m working to get to a place where I can quarantine. The chances that I have the virus are very low given I haven’t been anywhere near any place that has an outbreak.

-

What precautions are you taking, you fool traveler? A. While my chances of having and spreading are miniscule, I’m conscientiously washing my hands and following social distance protocols.

-

What are you doing? A. My main concern after not spreading is getting sick before I’ve gotten to a safe house. I wouldn’t want to fall into control of whatever they do with people found sick while on an airplane. For this reason, and because things are changing so quickly, I’m not wasting any more time getting to a safe house. It just happens that I’ve been caught out, without my own place, with a safe house a little bit distant.

At the border, Lisbon, Portugal

On the flight from Mexico City to London they have “Casablanca” in the selection of films. This film never gets old. Humphrey Bogart, a love trio, international intrigue and escape from oppression and capture. “Play it again, Sam.” “Here’s looking at you, kid.”

At the gate for British Airways flight 502 from London to Lisbon they hesitate. The gate agent, holding my U.S. passport, makes a phone call that goes unanswered. I assure them that I’m well informed that I’ll be allowed the visit. They allow me to board.

Ours is the only recent arrival at Humberto Delgado Airport in Lisbon. The border protection line for EU residents is short. There are three of us in the non-EU residents line for two stations. The two young women in front of me take longer than usual. They go digging in their bags and produce some sort of document which they show to the agents. They pass. I’m next.

Looking at my passport, the agent is immediately incensed. A United States passport:

“What are you doing here?”

I explain.

“Do you know the border is closed?”

No. My friend assured me that I could come.

“What does he know? Why aren’t you going to the United States?” He’s pretty well up and righteous with me now.

I see that this is going badly, but keep my best friendly face. I’m sorry, I thought our border was closed even to citizens.

“A plane left here yesterday with Americans returning home.” I don’t know, I shrug.

He types into his computer for a while before snatching up my passport and shoving back his chair to stand. “You’re coming with me. We’ll see what the supervisor says.”

I follow the agent across the vacant reception hall to a door that he badges through. He’s armed with a pistol and clearly unhappy. Is it usual for the people checking passports to be armed? I suppose. In the United States I think they are. In Uruguay they definitely are not. In any case, I’m in custody of an armed law enforcement officer who’s holding my passport.

We enter a room with no decoration and metal bench seats placed against grey walls. An authorized persons only door is held ajar by a stanchion. The agent who brought me goes through into a room behind a glass walled counter where two other armed and uniformed agents are at their desks. He has a brief conversation with them, hands over my passport, and leaves.

Book ‘em, Danno!

There’s a narrow window about head height along the top of an adjacent wall. I can see the city outside and the bay, a bridge. I’m still hopeful. I’ll explain again. They’ll verify with my friend. All will be well.

The agent who greets me from behind the glass, agent Abel, also has English. I have pretty good Spanish by now, but the Portuguese I’ve learned is hello, good day and thank you. We go through a similar line of questioning. He doesn’t want to know anything about my friend. He doesn’t want to call him. He doesn’t want to see the chat. He doesn’t want to know the address where I’ll be staying. He doesn’t ask anything about where I’ve been or make any assessment of my chance of being contagious. His only concern is that I’m there and that I don’t belong.

He tells me with some righteousness that the border is closed. I plead with him to make an exception for one person who has shown up with an invitation from a national, a place to stay, and a promise to keep quarantine. He confers with the other agent, agent Jorge, behind the desk. If agent Abel is good cop, agent Jorge is most definitely bad cop. He looks like a cop from the movies who runs down international drug traffickers. Come to think of it, that’s what he is.

They retrieve a thick pile of what looks like policy documents and consult them. After the conference, Agent Abel sits down at a computer and starts typing.

Every once in a while he calls a question to me from the desk. Then he tells me to sit down. I’m texting with my friend. He’s wondering whatever is the problem. I tell him they’re working to justify making an exception for me. This is hopeful, but I start to feel very cold. I put on the jacket that I have in my carry-on. I’m starting to shake a little. I stand and focus on my breathing, my eyes looking to the horizon out of the window.

At one point agent Abel asks the name of my friend and asks me if he is a national. Yes, he is a national. “Did you know that the border was closed, yes or no?” No. I relied on the information from my friend. I show them a text from my friend, that the person he checked with is someone in the government. “You should look at this,” I tell them. It’s to show that it wasn’t simply anyone who confirmed it would be okay, but someone official. This makes bad cop angry.

“That’s illegal,” he says. “You didn’t just show me that.”

I think he has decided that I am trying to influence peddle for special treatment. Hopefully, they’re deciding the case on its merits. That someone official thought it would be right, that ought to have merit. He doesn’t seem to agree.

The next line of questioning is whether I have means. I find this encouraging. I show him United States and Uruguayan currency amounting to a couple of hundred dollars. He dutifully records the denomination and quantity of every bill, and has me show him a credit card. Back to typing at the desk.

I’ll get you my pretty, and your little dog too

An hour has gone by and I’m invited to step behind the window and bring my things. In retrospect, this was a bad sign. I didn’t pick it up. He was very friendly and it seemed he simply wanted me to sit down to read and sign some papers. He’s typed a question and response record of our interview in Portuguese. He translates it for me. There are some details he hasn’t recorded correctly and he takes the corrections. One is that I knew the border was closed but relied on my friend who said it was okay. No, I tell him. I understood that the border was open for exceptions and that my friend had verified the exception. He’s getting impatient. I’m trying not to get him too testy.

He wants me to sign the interview. There are a couple last paragraphs that he didn’t translate. I read them as a statement that I received a translation. Sign, he commands. I ask if signing will help them make the exception. He says that it’s necessary if I want the supervisor to consider it. Okay good. We’re documenting the exception. I’m way too optimistic.

The moment I make my signature he whisks the paper away and places another in front of my saying that I’ve been refused entry. He has it in duplicate, a copy for me. He wants my signature on it now. Not later. Now. I try to look it over. He pushes it back to the desk. Sign. You get a copy.

On the third try he gives up and allows me to look over the document before signing. The reason they’ve checked is that I have insufficient documentation. What documentation, I ask? “The border is closed,” he tells me. That isn’t what it says, I tell him. Sign, he says.

I plead my case again. “If I had come here when?”, I ask them, they would have allowed me to enter. It’s been six days, they tell me. Six days. Well it’s an honest mistake. Can they make an exception?

Bad cop starts yelling at me about how everyone is ordered to stay at home, that he can’t see his family– all listed, each member. I respect that, I tell him. I’ll keep quarantine. No, they tell me. Sign. I ask for the exception. He waves a document at me and says the only exception is medical emergency. Then he asks if I have any official invitation. First I’ve heard that question. I refer to the messages on my phone from my friend. He doesn’t want to see that. That he call my friend. No. He wants to see some signed official paper.

This document he’s waving at me. I get the impression that it’s the new border policy document. May I see that? No. May I have a copy? No.

“What will happen?”, I ask. International law, he tells me, requires that I be given a place to stay, shower, eat and rest. They will take me to their hotel facility. The company is required to take me back to London on the next flight. (“Company” is what he calls the airline.) He’s now sounding very nice, reasonable, reassuring. I’ll be alright, he says. A night in our hotel and back to London tomorrow. I want to talk with my friend. He tells me I can call from the phone in the hotel, free of charge.

I sigh. I’ve lost. I sign. I ask for a copy of the interview that I signed as well. He refuses me that. I’m not sure why, but he clearly won’t provide it. Before signing I note that the document has a paragraph stating right to an attorney. Right, I think. May it not come to that.

Good cop takes me to another room like the first, only smaller. It’s completely unadorned with metal bench chairs around the perimeter. He also wants me to use the bathroom really badly. I don’t need the bathroom. Where is the phone? There will be a phone in the hotel.

When he leaves me I try calling my friend from my cell, but the wifi signal is too weak. I text to him that they’re keeping me for the night and I’m being sent back. He can’t believe it. I’ll call you from my room, I tell him.

It isn’t too long before two men come to fetch me. One is armed, the other not. They want me to take a mask and gloves. “Do you want me to wear them?”, I ask. No. We gave them to you. You have them. Okay. If you don’t want me to wear them, why do I need them? We gave them to you.

Heading out into the security area we badge through some doors to get to the entrance side of a security checkpoint. It’s a standard boarding security check. The bottle of tequila I picked-up from the duty free in Mexico City, for my friend, has their attention; but it’s good. No problem.

Walking along wherever we’re going, they’re friendly. Where are you from? The US, but I’ve been living in Uruguay. Oh? Geography test. Do you know where Uruguay is? Of course, it’s on the southern border of Brazil. Right, I say.

We badge through more doors until we get to a small SUV. Inside I ask them if we’re headed to the hotel. It’s not really a hotel, they say. “Oh my, is it a jail?” I ask them half joking. They laugh. No, it’s not a jail. It’s our facility here at the airport.

We drive through the maze of airport terminal internal service roads. Getting out, we badge through a door, ascend a flight of stairs, and wait outside of another door. My armed keeper is standing in front of a camera. In a minute, we’re buzzed in.

Hotel Humberto Delgado

Oh my. I see right away that this is no hotel. There’s a receiving desk and a narrow lobby with some soft, black, sitting room chairs. To either side of the desk there is a hallway with windows. Through the windows on one side I can see a courtyard area and then fifteen or so African people in a common room.

The other side is a mirror of the first, with fewer people. A short, middle aged man at the desk, with grey hair, salt and pepper growth of beard on his cheeks, and a jolly, stocky figure instructs me to take off my shoe laces and put them in my bag. Seriously? Yes, are you wearing a belt? Yes. Take it off and put it in the bag. He spots the cord I wear around my neck and wants that in the bag, too. Pockets? Put the contents in your bag. Money? Bring it here.

We catalog the currency as before, each bill accounted. They go into a brown paper envelope that the man seals, signs on three sides, and asks me to sign on three sides. I ask his name. It’s something like, Hugh and we have a little laugh while I try to get the pronunciation right. He’s friendly, but definitely in control, ordering me to do stuff.

Your phone. Write down the numbers you need, shut it down, and we’ll put it in our safe. Computer? Show me the screen. Good. Shut it down, we’ll put it in the safe. Your bags will go in our locker. When you want something from them, tell us. We’ll bring them out for you.

I’m thinking, this is jail. I’m not going to have my phone. I’ll have no way to do any research or talk with people. I ask him, “How will I contact people?”

We have a phone here on the desk. You can make calls.

Okay, when is the flight back to London tomorrow?

We don’t know.

Please find out.

It’s at eleven in the morning, but company doesn’t have to put you on it if there isn’t room.

Oh, there will be room, I say. What time do we leave here to get there?

We’ll have to see.

When will I know?

In the morning, we’ll have to see.

Did you talk with the airline?

We sent them an email.

An email?

Yes, to a special address for this purpose.

Can we call them?

They find two internal airport numbers for the airline, neither of which are answered. They’ve gone home. What time can we call them in the morning? At eight o’clock. Is that soon enough? Sure, but they don’t have to put you on that flight. Where are my checked bags? Company will have them.

While I’m copying phone numbers from my phone, Hugh coughs without covering up in the least. Just a cough, standing there next to me. I feel the hairs on the back of my forearm move. I feel the moisture of his breath beginning to evaporate there. I really can’t believe it and just freeze. “You just coughed on my arm!,” I say to the room in general. No one responds. Not a word. There’s nothing to be done but absorb the fact. Standing without moving for a moment, I take a breath and move on.

Hugh has been cataloging all of my belongings in duplicate on a form. He asks me if I have any dietary restrictions. He interprets my hesitation as misunderstanding. “For example, do you eat fish?”, he asks me. No. I don’t eat fish, nor cheese, nor milk, nor pork, nor ham. “There is no pork,” he tells me. Only chicken. Chicken is good, I say.

He has me sign the form and then tears off the bottom part, hands it to me, and tells me to keep it. I put it in my pocket. I’d like to call my friend, I tell them. Yes, you can call. You have five minutes to talk on the phone.

Five minutes?

Yes, five minutes on the phone per day. Each day you get five minutes on the phone. No more.

I call my friend. I tell him I’m in jail. He starts to tell me all sorts of things about how unexpected this is and how sorry and how wrong it is and what he can do to try to help. Hugh points out that I’ve used three of my five minutes. I have to stop my friend. I only have five minutes a day to talk, I tell him. They took my phone. I’m a prisoner. They’ve said I’ll go back to London tomorrow but then maybe not. I’ll call you tomorrow when I know more.

Hanging up, Hugh logs the number in a ledger, logs the five minutes, and has me sign the entry. He reminds me that I get five minutes a day, no more.

Stripped of shoe laces, belt, phone, computer, bags, and freedom, Hugh hands me a pillow and a compact plastic bag with a blanket. He also hands me a disposable toothbrush, tiny tube of toothpaste, and a round piece of soap wrapped in paper.

Do I get a towel?

It’s in the bag.

Seriously? I examine the little bag and wonder how.

Down the hall he takes out a big key and opens a grey door. We go through into the common area and he closes the door behind us.

Shared Quarters

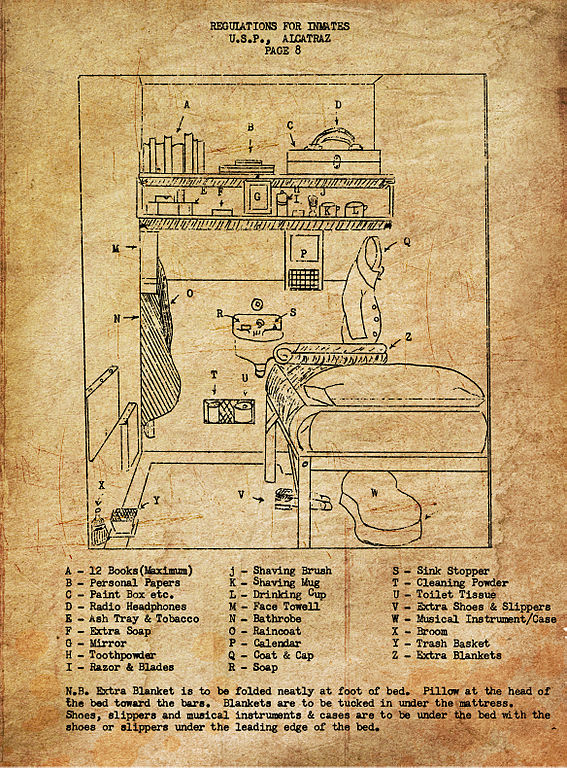

Here is a description of the hotel. The common area is a rectangular, grey room with drop ceiling and fluorescent lighting. Six white formica tables are spaced evenly, attached to the floor. Each table has four seats attached to its supports by a swinging metal arm. The floor is finished concrete.

On the side of the room where we entered is a stainless steel shelf with a few books stacked in a corner. A television on a swinging arm plays CNN at high volume. There is a large digital clock on the wall with red led digits incompletely rendered.

Another stainless steel shelf on the adjacent, longer wall contains a stack of single-portion cartons of milk.

One side of the common area has windows and glass doors that open into a courtyard. The courtyard has an overhang about three meters above the concrete floor, with wide radius curved, stainless steel edges to prevent climbing. Set back slightly from the middle of the courtyard is a rectangular concrete table with concrete benches.

Opposite the entry door, a short hallway connects two sleeping and bathing areas– one for men, the other for women. The men’s area contains six metal bunk beds with four centimeter foam mattresses covered in durable blue plastic. The walls, floor, ceiling and lighting are the same as in the common area.

A door next to the entrance to the sleeping area leads to a large bathroom with floor to ceiling tile and bright fluorescent lighting. On one wall is a stainless steel counter with four stainless steel sinks. Buttons on the wall deliver measured amounts of warm water with each press. The wall over the sink has a mirror, about head height, from one end to the other.

The rest of the room contains three toilets on one side and three showers on the other. All are divided by narrow, tiled walls. The toilet areas have swinging, partial height doors that will close. The toilets themselves are clean, but have no lids or seats.

The showers consist of a small dressing area with stainless steel bench followed by the shower area. Buttons on the walls of the showers deliver measured amounts of water with each press. There are no curtains. The floor of the area between the showers and toilets is puddled with water from the showers.

Cameras are present to monitor the hallway bedroom entrances and common room.

Hugh has me take my bedding out of the plastic bag and leave it on the bed. I’m pretty sure he takes the plastic bag. Back in the common area, he brings me a paper bag with some food. I’m hungry, and sit down to eat it.

He gave me two warm, rectangular containers. One has a thick soup which isn’t too bad, although I can’t say what it is. I eat half of it. The other has three portions: one of some sort of vegetable, maybe cabbage; plain cooked pasta spirals; a stack of two oval patties, grey speckled with white. I sample each, but have lost my appetite.

He also gave me two rolls in individual plastic bags, a single serving carton of milk, one of juice and a plastic bag with a slice of cheese. I drink the juice. The rolls feel stale through the bag.

At another table a young man of heavy build, with skin the color of ebony, a gentle, round face and friendly eyes is playing a card game with a woman with whom you wouldn’t want to get into a fight. He has a little English and tells me that he’s from Africa, trying to get to Italy, and that he’s been in the facility I think several weeks. I ask him if he minds if we turn-off CNN, where United States’ Governors are bickering about closing their state borders. He says no, that we aren’t allowed to turn it off.

I leave my dinner on the table in case my appetite comes back and go to make my bed. The sheets and pillow case are some sort of thin, light, synthetic gauze that is evidently disposable. The blanket is thick, warm, and soft. The towel is basically a dish towel. I decide to shower.

In the common area by the locked exit is a console with a button, camera, and speaker. I press the button. The speaker answers in half a minute and I ask to retrieve a change of clothes. We’ll be with you when we’re done with our dinner, the speaker says.

There’s one book in English in the little stack of books. I sit and read it while trying to tune-out CNN. I won’t identify the book because I’m going to say that it isn’t very good. It’s some kind of shaggy dog travelogue. Maybe something like this story.

Twenty minutes later, Hugh opens the door and summons me out. He has my bags out by the desk. While I’m fishing-out a change of clothes and my gym shorts he notices a leather string bracelet that I wear around my wrist. He asks me to take it off and we have a joke about how I got that by him. He also checks the band of the gym shorts for a string, which they have, but he’s okay with it because it’s sewn in and can’t be removed.

Secured back in the common area I realize that I’m not going to eat anymore and throw everything away with the exception of the rolls in their bags and the carton of milk, which I put on the back table.

The single button of the shower provides warm water, thankfully, after a few presses. After drying myself with the dish towel and dressing in gym shorts, tee shirt, and shoelace-less sneakers, I decide to try sleeping.

Escape planning

Sleeping is difficult. My mind keeps replaying the scenes of the border encounter; planning the morning, what I want to ask my friend, with my five minute phone call, to productively help; figuring how to get information about flights and ensure that I’m on one; worrying that I’m locked up incommunicado with no freedom to leave.

The hour comes when they turn out the lights, but I’m still awake. Turning out the lights doesn’t make the room dark. There are two bright emergency night lights near the floor which keep the room illuminated. At least the room is warm. Maybe a little too warm.

At about three in the morning my mind arrives at a plan. I’m a guest. They have told me they are taking care of me and that I’ll leave promptly on a flight out, first available. I’ve decided to treat it that way. In the morning I’ll insist on the care, answers, and arrangements they have promised. This seems to relax me. It’s the last thing I remember before falling, exhausted, asleep.

I wake with a start as the morning host, a short but well muscled, balding man in his thirties, wakes us by calling out something. In the hall just outside the locked door, he has a breakfast meal for each of us, and a roster. I take my meal and he has me sign for it. I try to go to the desk to conference, but he blocks me. Is there anyone at the desk? He says, no.

I take up a seat at a corner of the common area where I can see through the window to the courtyard, then through another window to the reception area. Breakfast is a box of juice, of milk, a stale roll, another slice of cheese, and a little tub of preserves. I spread the preserves on the roll and swallow it down with the juice and some water.

I try do decipher the clock. The hour should be eight, I think, but all of the sides of the digit aren’t lit. When should I insist on a call to the airline? Pretty soon. They said that the flight to London is at eleven.

There are people moving about in the reception area, around the desk. The button under the speaker summons a voice. They ask me to stand back from the camera. What do I need? I need to access my bag. I try for a tone that is friendly but assertive, as if I’m speaking to a hotel reception. I am their guest, not their prisoner.

While using my comb and deodorant I try to get some answers about the day plan. I’m not going to use my five minute phone call yet, but hope to get them to try the airline again using the numbers from the night before. That isn’t going to happen. Not now and I can’t get any commitment about when.

I ask if I can take my safety razor to shave. No way, he tells me. I’ve had people try to cut their wrists with those. No doubt, I think.

I see that there’s an essential conflict here. For me, I am their guest. They have taken responsibility to care for me and put me on a flight as soon as possible. I’ll take the word of agent Abel on that score. For my keepers, I am their prisoner, an illegal, and committed to follow their orders. This is going to be a delicate balance. I resolve to remain firm and see what the limits are.

Back in my seat with a view, I see that there are new arrivals. There is a pair of men who are eventually shown into the common area and then go out to the courtyard to smoke. They are chatting in Portuguese in a tone that sounds like dark humor. They sometimes chuckle darkly. I perceive that they’re making the best light of their situation as they can.

The sun has begun to light up a patch of the courtyard on the opposite wall, and a corner of the bench at the table. I sit there in the sun to raise my spirits and read the book. Pretty soon I’m called to the reception area. There’s a man on the phone for me.

A promise, and new arrivals

He identifies himself by name, and as the person organizing my return. Evidently I’m still a little off balance because I don’t catch his name or get it written down. He asks me where I want to go. I want to return to London if they are allowing entry, or to Miami. Miami, he says. Good. That is one of the possibilities. I get him to make a commitment to call me back within the hour, with status.

Hanging up, I ask to make a phone call. There are four other people in the room. There is the woman behind the desk who handed me the phone and took it back. There is the man behind the desk who retrieved me from behind the locked door. There is the man who woke us up and gave us breakfast. There is a young woman sitting in one of the chairs.

I ask the man who retrieved me to allow me to make a phone call. He tells me to sit down and wait. While I’m sitting I get to witness the unfolding of a scene very much like my own from the night before. The man who brought breakfast is cataloging the belongings of the young woman. She is writing down phone numbers from her phone. She’s in the same state of half realization that I was. It’s dawning on her that she is being made prisoner; but she’s not quite ready to believe it.

While she writes down phone numbers the other three begin chatting with each other in a friendly way. I’m not able to understand entirely, but do pick up that they are talking about fruits. The man who summoned us for breakfast is speaking rapturously about various types of fruit. His face looks sweet and passionate and the others are responding warmly. There is a sense of community and love among them. I see their humanity, and wonder if I’m experiencing Stockholm syndrome, where prisoners begin to feel positive feelings toward, and sympathetic with their captors.

Sometime during the process a second person is brought for processing and given a seat on the opposite side of the reception area. The young woman has reached the point where she can make her phone call before being shown into the lockdown area. Her call doesn’t go through. It is met with a recording. She pleads with the man who brought breakfast, and begins to break down in tears.

They try the call a second time with the same result. He logs the calls in the log book and has her sign. My god, I think. Those were two of her five minutes– two incomplete phone calls.

Once they are inside the lockdown area, the man behind the desk decides that I’m not going to make my phone call. Why not? Because there is another person here to be admitted. I can make the call when they are done with him. I shrug and let him lock me back up in the common area.

Not much later, the man returns to retrieve me again. There is a phone call for me. The man who called me earlier informs me that he is working to send me to Miami via London and that I can find out in London whether they will let me enter. I thank him and hang up.

On the way back in, the guard wants to know what he said. He’s puzzled that he had called just to tell me that. His puzzlement sets me wondering.

Sitting down and thinking, I’m paranoid that the sole purpose of the call was to fulfill his promise to call me back. I hadn’t extracted a new time commitment. Worse, I hadn’t asked him when is the next flight to Miami, because now he’s attached the flight to London to a flight to Miami.

Part of the problem is that I’m still thinking in pre-pandemic terms. There are flights to Miami three times a day. Not. It could be once every few days or even less frequent. This shakes me up a little.

I distract myself thinking about what I would do anyway, if they allowed me to enter the country in London. I could go out to Plymouth or Falmouth, rent a place to quarantine, and later look for boats there. There are lots of good ocean going boats in Falmouth, where Sir Robin Knox Johnston launched his solo round the world, nonstop effort in the sixties.

Obviously, I haven’t really absorbed the changed state of our world.

The clock is ticking

I press the button and ask to speak with the man who called me again. They ask me to wait.

Twenty minutes later I try again. The clock is ticking. They haven’t been able to reach him, yet. Wait.

I go back to the sunny place in the courtyard and sit down in the sun to read and calm myself. The sunny place has grown larger with the movement of the sun. Now a good number of us are out there, including the two men who arrived in the morning, one of them smoking. The African man from the night before sits down on the bench next to me and we nod greetings.

I’m still trying to keep extra personal space not to risk infecting the others if I happen to have picked something up in my travels. But I wonder why. In these conditions it’s almost inevitable that I would share if I was shedding the virus.

The young woman who arrived is sitting with her back to me in the common room. I can see through the window that one of the women already here is sitting opposite to her and consoling her. Eventually she feels collected enough to step out into the courtyard.

She stands uncertain, by herself, looking but not seeing, trying to take-in her surroundings but not really succeeding.

I catch her eye and stand up, indicating my seat in the sun and inviting her to take it. It is a small gesture to offer her a small thing that might help her spirits. I’m surprised, but she accepts, and I move to the other end of the bench next to the African. He smiles. I ask him again where he is from. Africa. No, where in Africa? He is from Sudan. And you are trying to go to Italy? Yes. I feel a little bit stunned. Things must be really bad in Sudan if he is trying to get to Italy, where they’re piling up the bodies of the dead.

Looking past him, I ask the young woman if she is okay. She speaks English and, unprompted, tells me her story. She has arrived on the morning flight from Sao Paulo. Her boyfriend assured her that she could come. She can’t contact him because they always use Whatsapp. He doesn’t buy any regular phone minutes.

I try to give her some positive things to latch on to. You speak Portuguese, I tell her. That is an advantage. They will most likely put you on the next flight back to Sao Paulo.

Deportation

There is a tapping on the glass between us and the reception area. It is the man who has been retrieving me for phone calls. He’s tapping with the key on the glass and indicating me. My phone call! I get up and go to the door, so excited that I don’t even excuse myself from the others.

On my way I get out my slip of paper with phone numbers and when the woman behind the desk hands me the phone, I ask for a pen. This time I’m prepared. The man asks what I wanted. I apologize and tell him that I didn’t get his name. Ricardo. Thank you, Ricardo. When is the next flight to Miami?

He tells me that someone will be there to retrieve me within the hour. I will be on a flight to New York with a connection to Miami.

I’m so happy and relieved. I’m leaving! There could be no better news. The man who is ushering me in and out instructs me to go get my things and waits in the common area. I come out with my change of clothes and he sends me back for the bedding, everything.

I’m just barely fast enough for him because, as I emerge from the sleeping area he’s on his way in to find me. Clearly he’s uncomfortable waiting in the common area. It occurs to me that he feels nervous around his prisoners, or guests, or detainees, or whatever you want to call us.

He has me leave the bedding and pillow in a box of the hallway between the locked door and reception. At reception, he has me sit down while he retrieves my bags and property. With that, he asks me to sign the form saying that I’ve gotten everything back.

From my point of view, I haven’t. He hasn’t opened the envelope. I haven’t put everything in my pockets or away in my bags. From his point of view, he wants that signature. I’ll get my stuff when I’ve signed. He’s a little insulted. “You are in Europe, now”, he tells me. (I guess he is implying, not the United States.) “You will receive all of your things back.” I sign.

Two armed agents arrive while I’m putting myself together and they want to leave immediately. I haven’t gotten my shoelaces back into my shoes and indicate that I need to do so. One says, no. The other says, yes, looks at his watch and says something in Portuguese to the first that I somehow hear as, “we have time.” The first says, okay but hurry.

I try to put the laces in my sneakers as quickly as I can. Other than I’m shaking a little. Other than I don’t lace my shoes every day, I’m doing alright. The officers try not to stare at me until I finish, and we leave.

On my way out the man behind the desk asks me if I want to make my phone call. Well, yes, but no. I want to leave. “I’m leaving now,” I tell him. I look back into the courtyard. The others are talking. The young woman and the African are seated where I left them.

I didn’t get to say goodbye, I think, nor wish them well. I think maybe that’s for the best since I’m the lucky boy this morning. I hope my departure gives them hope for their own, and soon.

Air Portugal

We ride to a gate where a big jet from the Portuguese airline, TAP sits bright, polished, looking new, and ready to go. I’m ushered up stairs of the jet bridge where an agent of the airline allows us through the door. I can see the pilots through a window, in the cockpit, preparing for departure.

Down the corridor I can see the open door of the plane and flight crew preparing. Up the corridor, I see the glass door behind which people sit in the gate waiting area. I’m going to be on this airplane, I think, with relief. They’re going to put me on this plane and it’s going to New York.

I ask about my passport. The agent who allowed me to put on my shoelaces shows me a brown envelope and a boarding pass. He says the boarding pass is for the connecting flight to Miami. The envelope has my passport. The flight crew will guard it on the flight to New York. They will hand it to me when I get off the plane.

I ask about my checked bags. “Company will take care of those.”

We are early. It is ten or fifteen minutes that we have to wait, during which time I move around trying to get a usable wifi signal from the terminal in order to update my friend. I ask the airline agent if there is wifi on the plane. He tells me there is, but that I’ll have to purchase it. That’s good enough, I tell him, and thank him.

Someone gives a signal and the armed agents escort me to the door. They hand the brown envelope and boarding pass to the first officer. Some of the flight attendants are there smiling to greet me. I ask if they will show me my passport just so I’m sure and can relax. They’re bemused. Of course it’s my passport. They’re not putting me on this plane without my passport. But, they accommodate my request. I express my relief and thanks.

My seat is in the very last row. The flight attendant is welcoming and smiling and says I can move later if I like. The flight is nearly empty.

The plane is a brand new Airbus 330. At least it feels like it’s brand new, and there’s a whole fleet of them outside the window. Well Portugal and Airbus are getting along fine, I think. And the Portuguese people have a fine fleet of top notch equipment. The wifi system takes my money. I begin contacting friends, figuring out my plans. I’m back on my own. Free.

Arrival, U.S.A.

Well almost. I’m told that I must wait to be the last off of the plane. While the next to last passenger gets himself together to deplane with carry-on, personal bag, CDC and declaration forms, mask, and gloves, I chat with a flight attendant. She tells me that this was the very last flight for a while, at least until May. They’ll be returning with a few Portuguese nationals and then shutting down.

My god, I think. I know I’ve been riding on the tail end of events but had no idea just how very close events had come to catching up with me and good. Wow, I was lucky, I tell her. It’s strange to feel lucky having met with such a mishap, but here I am. I’m in Newark, New Jersey getting off of a beautiful Airbus 330 talking with friendly people who have shuttled me across the Atlantic from Portugal.

On my way out, a young woman holding the brown envelope verifies my name, looks at the photo on the passport, and hands it over with the pass for a United flight to Miami. I’m free, I think. Now I’m finally free.

Actually, still not quite. I have to pass a CDC check of my temperature and present myself before a border patrol agent. The CDC boys take my temperature and pass me. The border patrol agent asks me how long I’ve been out of the United States. “Oh, about two years,” I say. He stamps my passport and mumbles something to the effect that I’m all set. Or maybe it’s, get going out of my sight. Either way, I’m good. I’ve escaped the crack between borders. I’m admitted to the United States of America.

Postscript

I treat myself to not just any hotel, but a good hotel, splurging a little. The hotel shuttle driver is friendly. The lobby is spacious and grand. There aren’t many people around. The lounge furniture has been stacked into a corner to create additional space for social distancing and discourage congregating.

The marble floors are shining. The carpets are thick. The receptionist takes my credit card and hands me a key.

The room is warm, clean, well appointed and decorated. I treat myself to a long hot shower and wash and wash. I even wash my shirts and underwear that I had worn in the lockdown. I’m only half aware what I’m doing, a sort of symbolic cleansing. I only know that it feels good.

It’s only four in the afternoon, but my body no longer knows time. I lie down in a huge soft bed with high thread count sheets and a thick soft cover to warm myself. Cozy. Safe. All it takes is money. And fall asleep.

Post postscript

My bags caught-up with me in upstate New York, via FedEx, about two weeks later. Somewhere after leaving them in Mexico City with British Airways, they had been thoroughly “tossed”. The condition of their contents testified to the term. Everything had been removed and then replaced in random disarray. There were some things missing. Odd things, like a pair of winter gloves and a knit scarf; a cheap Sears multimeter that I’d picked-up for inspecting boats. The search had been most thorough. For example, a sealed envelope that I carry with some documents had been opened. Was it the SEF in Lisbon looking for a reason to keep the strange American for longer? Who knows?

Post post postscript

I don’t know why we still keep borders, and nations, and fight among ourselves. It’s a remnant of our tribal past. We’re still tribal animals. We still think of us and them. Our people and the others. It’s how we’re wired, I guess.

I guess I can’t answer for anything different, or visualize how we’ll be when we’re all one tribe. What I do have is this, which came to me from an author with whom I’ve crossed paths in Uruguay. Let me share it with you.

Vida

Cuando me prohíban tus abrazos

Tus miradas tus sonrisas tus besos

Buscare rescatarte vida

Esperare que me rescates vida

Porque sin ti dejaría de existir

Tan triste como resignarme a no amarte

Tan solo como desde aqui vida te escribo

Pero sé que ni el más cruel de los dioses

Puede prohibirte vida

Como tampoco que el agua llegue al rio

O que de la planta nazca una flor en primavera

Te esperare paciente vida

Con las ventanas y las puertas abiertas

Hasta ver puntual a la paloma llegar con el olivo

Y entonces saldré urgente con mi amor a festejarte

Te encontrare caminando, en las calles, los mercados y las plazas

Entonces te recuperare entre abrazos, sonrisas y besos

Mi querida vida, mi querida gente

– Eduardo Rejduch de la Mancha

Until the time when the dove appears with the olive branch, here we are adrift in the flood. May your ship land safely.

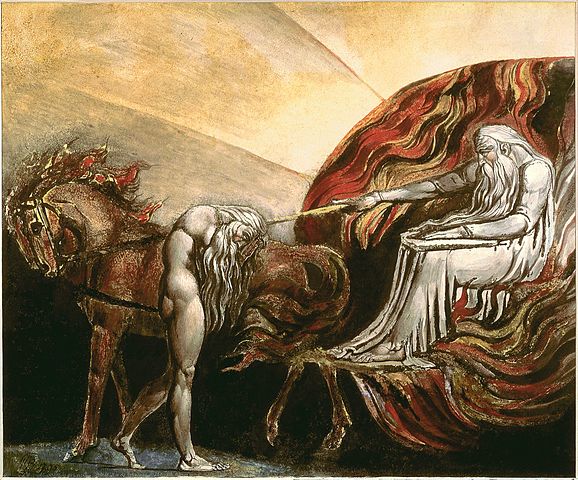

Image credits

Images from Wikimedia Commons: