The Magenta Line

Mostly I write about my sailing adventures in less than perfect Spanish, over at Brisa.uy. Here’s a story in English for my English speaking friends.

Every accident has a chain of events that lead to it. On this night I was fortunate. There was no damage.

Leaving Panama, my single, most ardent desire, that which carried me through all sorts of misadventures, was to visit Cozumel and try scuba diving. That, and to eat Mexican food again. That, and to visit the sites of the lost, great civilization of the Maya.

Cozumel

Looking at Cozumel on the charts, I found only one anchorage and one marina. The island is beach and surf on the east side, facing the Caribbean sea. On the west is a channel a few miles wide, sheltered from the sea swell and trade winds. The island is steep-to all around. According to the sailing directions, the two-hundred meter depth line is no more than half a nautical mile offshore, all around. The island is surrounded by a narrow underwater shelf with coral reefs, then a steep, underwater cliff.

There is only one bay, on the west side, very small– Bahía Caleta. “Caleta” means cove. It is little more than a cove. Inside this cove, the entire shoreline is boats on piers, including some private marinas and the public marina, Marina Fonatur.

There was a Fonatur marina in Baja California, at Puerto Escondido. It had excellent services for transient boats– floating docks, friendly staff, a shop, restaurant, bar, laundry, and showers. This was the picture I had for Marina Fonatur in Cozumel. The pictures on the web looked nice. I felt no reason for concern that I couldn’t get hold of them on the phone.

Passage

I arrived in Cozumel after three nights at sea: a fairly brief passage. I had left on Thursday afternoon. The weather had been mostly marvelous. Friday night and into Saturday the wind came up fresh. This is a little strong, but I prepared well, with just enough sail, that the ride was not terribly uncomfortable.

Saturday morning the mount for the autopilot broke. I repaired it hove-to in fresh wind and six foot seas, under a bright, clear morning sky. I sat at the tiller steering for most of the day, about nine hours, with an hour hove-to again to rest and have something to eat. By nightfall, Otto the autopilot was again in charge of the tiller.

The morning of my arrival there was a squall, very brief. Cozumel is very low. I didn’t see it until I was only miles from it. I was little further west than I needed to be. No big deal. My ground speed all morning had been much greater than the speed of the boat. A strong current– I estimate three knots –was carrying me up the channel toward the port.

Arrival

On arrival I tried to call the port captain and then the marina without any response whatsoever. This was freaking me out a bit. Either both my radios were not functioning, no-one was listening, or I was being ignored. There were dozens of boats, mostly launches and a few large catamarans. The boats had scuba divers, snorkelers, fishing adventurers, and people out for a ride on the coast. The drivers of the boats treated me like a bad driver. Some yelled criticisms or instructions. Others waved back at me in a slightly bemused manner. It was clear that I didn’t belong there.

The current in the channel roils at the shelf, where the lesser, shallow water current meets the faster, deeper current. Big cruise ships take moorings right up against the shore. There were four or five of them, giant, floating hotels, one with a water park on its top deck.

On the advertised VHF channel for the marina someone was putting music for five or ten minutes. Some other boats, ship to ship, were talking in foul language about the current. The marina was not present on the channel nor on the universal hailing channel sixteen.

I decided to prepare my lines and fenders on one side and risk the depth of the entrance to the marina. I could see bottom right under the boat in crystal clear water. A sand bottom, reassuringly. The entry was narrow, very active with boats entering and leaving. (I was going too slowly for them.) The marina docks were poured concrete with inadequate, nearly decorative plastic bumpers.

I started down a channel between the piers only to see seven tenths of a fathom under the depth sounder. The depth sounder is a few tenths of a fathom under the water. The depth of my keel is one fathom. I had inches under the keel. I stopped, tried to back. As the wind brought my bow around I entered the last slip and let the wind push me gently alongside of it.

Still no-one from the marina had responded to radio calls. No staff had seen me enter. No staff had come to greet me or help with lines. A passer-by whom I stopped tried to put me on the phone with an agent to process my arrival in Mexico. I wanted to talk with the marina first.

After half an hour a security guard came around. He was a young guy from a private security company. He told me I had to move; that the slip belonged to a tenant. He pointed to a narrow slip on the next pier, next to another sailboard. You can go there, he said.

I said fine, but where are the marina staff? What are the prices? How do I accomplish the entry paperwork? He knew none of that, but called someone who promised to come around sometime that afternoon. Meantime, he wanted me to move.

By now the wind had increased. It had blown me into the slip and was now holding me there securely. It would be a tough exit. It was going to be chancy entering the other slip as well, given the strong crossing wind that would blow the boat sideways. I asked him to get help to launch me from the slip I was in and take lines at the other slip. He said, no problem, that he would help me.

I asked him about the depth at the other slip. He said, “seven meters.” I told him there was no way there was seven meters (about nineteen feet) depth over there. Maybe you mean seven feet? Oh yes, he said, seven feet. Good, so how are you going to help me launch and then get to the other pier in time to help me land? Well, he said, I’ll go over there and wait for you. You can launch yourself.

Departure

Clearly I was not wanted. This marina was not set-up for transient boats. There was no staff and no service. It was a working marina for commercial tenants– fishing, tour, and dive boats. The number of recreational boats I could count on one hand.

I felt trapped, because getting myself off of the dock without assistance was going to be very sketchy. I felt alienated, because everyone was treating me like an alien, or at best a curiosity. I felt threatened, because no-one was coming forward about the costs of processing my entry paperwork and staying in the marina. It felt certain that those costs would be an unpleasant surprise. It has happened to me before in Mexico that services rendered without first asking the price come with a highly inflated price after.

I felt disappointed, because this Marina Fonatur was nothing like the Marina Fonatur I had so pleasantly enjoyed in Baja, in Puerto Escondido. I felt discouraged, because the scuba diving I had so looked forward to wasn’t possible, because there was no adequate place for me to park. I felt frightened, because going back out to sea for another night, unexpectedly was going to test my endurance.

Everyone I had talked to about Cozumel had asked me about Isla Mujeres. Isla Mujeres is the popular, go-to stop for cruising boats. Now I was in a pickle and I wanted out. I mapped the route. It was a little over fifty nautical miles. The entrance to the shallow bay was about thirty five nautical. Can I make those thirty-five nautical miles take fourteen hours, in order to arrive the next morning with daylight? If I traveled at two knots, maybe. Or if I take a detour out to sea after clearing the north end of the island. I planned to do that. Sail out to sea and sleep. Sail back in the morning to enter the bay.

Not having internet, I used the Garmin to pull a spot forecast. It promised fifteen knots gusting to twenty from the southeast. That is not pleasant but not impossible. Seas will be a little rough. I’ll run double reef and staysail.

Departing the slip was indeed sketchy. I set-up the boat halfway out of the slip. I tied the forward tightly to the cleat, with my big ball fender in-between the boat and the concrete. Then I cast all lines but the forward one and motored forward onto it. This brought the stern out, away from the dock. Quickly, before the wind pushed the stern back, I ran up to the bow and untied the line from the cleat. Free of the dock, I backed out. The stern always walks to port when backing. This turned the bow toward the dock. It kept close to the concrete wall as the boat backed away. From the cockpit, I was sure that it was going to scrape. It must have missed by inches.

At three in the afternoon, I motored out the narrow channel for Bahía Caleta into the big channel between Cozumel and the mainland. I was off to sea again after hoping to celebrate the end of the long passage from Panama to Mexico. It was disheartening. Dashed hopes and unrequited love– two risks of living with optimism. Hoped for blessings banished, I was pressed back into living in the present. The present was to keep on sailing, sailing, sailing. The present was another night making catnaps at sea and sailing circles to make a second landfall with daylight.

Sailing north

I put-up only the triple-reef main in the moderate breeze and shelter of the island, where the sea was flat. I was in no hurry, after all. In fact, I wanted to sail as slowly as possible. This is a rarity, I thought. The slower the better. Haw often do I feel that way?

With hardly any sail and the boat barely pushing a wake I quickly saw that there had been a flaw in my calculations. The current in the channel was adding three knots to my speed. I was seeing five knots over the ground. I would be to the Bahía Mujeres entrance at ten in the evening, or what to me is ten at night. We sailors are early risers. By ten, we’ve had one or two cat naps or gone soundly asleep, depending conditions.

I let myself sail to the north end of the island. There the water started to become uncomfortably rough. Given some fetch, the wind was stacking-up waves against a big swell coming down out of the gulf, against the current. I decided that sailing wasn’t going to help get me there more slowly. I decided to heave-to on the triple-reef main.

Inside the cabin, the boat is treacherous. Standing, even bracing myself, I get thrown against one side of the boat and then the other. Lying down, it’s impossible to rest. Without maintaining braced position I’m tossed occasionally against the lee cloth. Brace position– on one side or the other with the top-side knee drown up and the bottom side arm bent out front –isn’t so relaxing. My muscles keep working to hold myself steady.

I’m anxious. The sounds inside the boat are spooky– howling, sloshing, a wave occasionally spanking the boat hard with a loud wallop. I just lie there working to relax.

One of the cruise ships that was moored at Cozumel overtakes me on its way north to somewhere. It passes close-by, about one nautical mile away, upwind of me to the east. It’s a beautiful sight. I brace myself in the companionway, head and shoulders poking outside, to watch it go by. I always think of talking with the ships on the radio, just for company. Then I think, ah well, they’re busy. They don’t want to talk. I’m probably wrong about that. Some captains might find us slow moving little sailboats to be a nuisance. Others might be as curious about me as I am about them.

After the cruise ship goes by I somehow manage to make a thermos of instant coffee without scalding myself or otherwise spilling it. I suit-up with raincoat and harness to sit outside in the cockpit. It’s much more comfortable out there. The fresh air is nice. The wind does not feel so bad as the howling below suggests. Seeing the waves, and sitting braced with my back to the wind– it’s pretty awesome. The waves are dark, of course. There is no moon. There is sky glow from the urban sprawl of Cancún. The waves cause the coastal lights to appear and disappear. I get a command view followed by a wall of darkness.

Planning, and making new plans

The calendar on the iPad that I use to navigate sounds a reminder that the twenty-four hour wind and wave forecast is about to come. The United States Coast Guard broadcasts it on the HF radio from New Orleans. This single document is the single most useful tool I have for planning passage once passage is underway. It tells me what the wind will be doing when I wake up in the morning. Sometimes I can get it. Other times it won’t come-in. Tonight I get it.

What it promises is wind of twenty five knots. Twenty five knots of wind is nothing you want to piss at. It causes me to reevaluate my plan to delay entry until morning. It causes me to evaluate the lesser of two evils. The first is navigating the shallows of the bay in the dark, trying to identify lights to validate my position, unable to see shoal nor reef. The second is navigating into the shallows out of high seas and strong winds and with light to see by.

The second also involves sailing south again against the current in order to delay. If I get downstream of three knots of current I’ll have a devil of a time getting back upstream. By no measure must I allow myself to be north of the entrance to the bay.

Another option is to keep on sailing. With that kind of wind, continuing through the Yucatán Channel and making passage north of Cuba to Dry Tortuga would have me in the United States of America in only three days. I measure it. It’s three hundred miles, same as I just made from Grand Cayman.

To be honest, the only thing that stops me is the thought of a full night’s sleep and Mexican food. Peripherally, one more thing. Peripherally, but it’s important. I don’t have a full internet weather briefing for the route over the next three days. The twenty-four hour wind and wave chart showed a gale blowing in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

What is the new plan? I’ll make the entrance in the dark; get the hell out of Dodge City and into Pasadena. It’s terribly risky. See how one problem can lead to another? I’m keenly aware than I’m constructing an accident chain. Fleeing the discomfort of the situations at Cozumel has put me into a different, perhaps more risky situation.

I put myself under sail again, because lying hove-to no longer serves. The quicker I get to the bay entrance now, the better.

Bahía Mujeres

This current I’m riding cuts a deep channel through a shoal that extends north of the island of Cozumel and over to the bay of babes. Er, that is Bahía Mujeres. The island, Isla Mujeres is the barrier island for the bay. To the northeast of it is the Yucatán Channel. To the southwest, the bay, the mainland and the urban resort town of Cancún.

Depths inside the bay are at most thirty feet. There is an extensive, shallow shoal southwest of the island. There is extensive shoaling off of the mainland. In between, a channel. The chart shows red and green buoys and yellow hazard buoys that mark the way. It promises a bright yellow flashing ODAS buoy at the mouth. It promises a red and green flashing buoy marking the south side of the channel entry.

At half past eleven at night I’m at the decision point. Sail south or sail to Dry Tortugas or head for the safety of a harbor. Seems like a simple decision, right? Yet there I was, deciding. Navigating an unfamiliar field of shoals in the dark is so onerous that an unplanned, three day sail to Dry Tortugas feels like a viable option.

Sailing south to delay until daylight would be tough. It would mean making at least four knots under sail and without fail. This in rough seas and high winds. Raising the staysail and shaking out a reef (in the dark) would do it. The boat would sail briskly, well heeled, bashing the waves. It would be bashing and splashing, beating the daylights out of the rig, shaking up the inside of the boat, and punishing this sailor. In short, it would be a shit show.

Turning into the bay means putting the wind at my back. That will be nice. The waves will be pushing me along as well. It will be a piece of cake. It’s also an act for which there is no turning back. Trying to turn around and come out, motoring into wind and sea, I would make little headway. At best I could make a knot. There I would be again: bashing and splashing, beating the daylights out of the rig, shaking up the inside of the boat, and punishing this sailor.

Turning into the bay requires commitment to the unknown. We like that sort of living, don’t we? We do this to skirt the slow death of the known and comfortable, don’t we? I take a deep breath, start the motor, heave-to to drop the little bit of mainsail I have flying, and then motor gently northeast into the channel, downwind, with the sea swell and wind waves pushing me along.

Did I say there would be lights? The chart promised lights marking the channel. All I can see are city lights on both shores– Cancún to my left, Isla Mujeres to my right. That’s to port and to starboard in ship speak. Each has a light house. Their flashing lights amidst the steady lights suggests that they are present and functioning. They are where I expect to see them.

If there are any lights on buoys marking the channel, I never see them. They could have merged with the city lights behind them, but they flash. They could have been always hidden in the trough of a wave when I was looking and they flashed. Most probably, they are not there.

There was a prominent, solid light onshore that I chose to steer by. If you trust that it’s the correct solid light among all of the others on shore, you can steer a magnetic bearing to it in order to keep the center of the channel. It is prominent. You can do that.

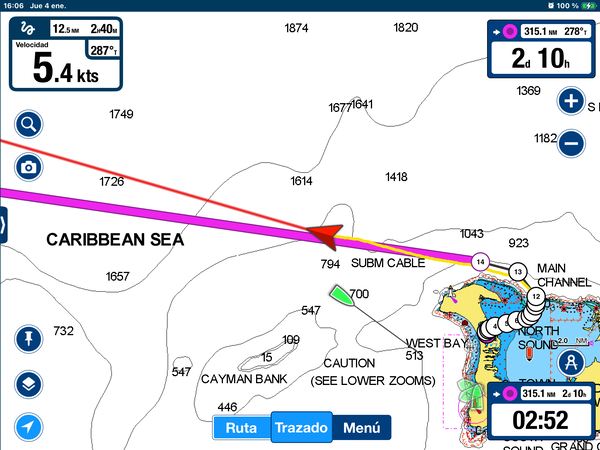

You can also, additionally or primarily, follow the magenta line. Every GPS chart plotter since the dawn of civilization shows the route you’ve plotted with a magenta line. I think Garmin started it. My Navionics plotter on the iPad does no differently.

Otto was able to handle the following sea for a short time. Waves, as they reach the shallows, build steeply before evening out. If the waves are powerful enough or large enough and the shallows are shallow enough, the waves will break, just like at the beach.

These waves were not threatening to break, but they did get steep. They would push the boat occasionally sideways, forty-five degrees off course. It takes some force on the rudder to straighten it out, have the boat surf the wave instead of being turned broadside by it. Yeah. I had to take-over from Otto.

I had told myself it would be like that. I had told myself it would be just like entering Bocas del Toro. Sometimes I get it right. We surfed a couple of dozen waves coming into the shallows and then everything calmed down.

It’s amazing and wonderful what GPS has done for us. Any back yard gardener can navigate using GPS. The position is ultra reliable. We trust it. The hydrography of the chart is also extremely reliable. The civilized part, lighted buoys, the charts can’t keep straight because the organizations that place them and report them don’t report them any better than they place them. The natural part, depths of water and contours of land– the parts directly observable –they are are generally spot-on. This is also the part that is most risky to rely on, I think. Steering my boat through the dark water, I sorely missed having a visual on this shoal, that reef or that rock. In fact, I felt insane doing so. This, I thought, is madness.

I steered by the shore lights, peeking under the hatch frequently to see that my little boat triangle was on-top of the magenta line, making adjustments as needed. I slowed down when things got tight. I kept an eye on the depth in order to regulate my speed: shallower == slower! By the magenta line and skill in steering the boat to it, I arrived in the dark, in the anchorage, in a small bay on the south side of Isla Mujeres behind a reef and a spit of land.

Dragging anchor

While there are no waves in the anchorage, there’s still wind. Wind takes hold of the boat and tries to turn it sideways. It wants to push the boat sideways downwind. Driving slowly upwind with motor and tiller, when the boat starts to go sideways you have to correct quickly. At a certain point there’s no getting straight again without drastic amounts of rudder and power. The wind wants the boat the way it likes, and it likes it sideways.

When anchoring, you drive the boat into the wind, let it come to a stop, and then let the wind bring the boat back. As the boat starts back you drop anchor. This way the the boat pulls the anchor through the water as the anchor falls, keeping the anchor oriented properly to grab hold when it reaches bottom. My boat has the anchor on the starboard side of the counter-stay for the bowsprit. In order to keep the chain from grating on it, I always cheat the boat a bit to port as it slows upwind. Then the boat falls-off to port and the chain has clear running.

All of that is color, that is to say irrelevant, other than to note that in normal wind all of that happens fairly slowly. In fifteen knots, as was blowing here at Isla Mujeres in the wee hours of the morning, all of it happens very fast.

The anchorage was not crowded, but well populated. I had to choose a spot related to the other boats and to depths and location, etc. In the dark, I was surprised by a boat that I didn’t see until the shore lights put it in silhouette. Please, people. If you’re not running your anchor light for some reason, get it sorted so that you are running it. About half of the boats in the anchorage were dark.

I got myself in position and went forward to the anchor, started freeing its four restraints. Yes, it has four. Then the boat would be blowing down sideways. Usually I put Otto in charge, make everything ready, and then go back to organize the final approach. The hour and the oddity had me forgetful. I dropped anchor on the third circuit.

When the anchor hits bottom I feed-out three or four times more chain, then snub it with a hook to set the anchor. Tonight, the wind blowing the boat was enough for a set. The boat stops. My foot on the chain feels the chain come solidly rigid. Next I add more scope. Next I back down in reverse to see that the anchor is indeed holding well. Next I put the snubber on. I shut down the engine. I set an anchor alarm. I breath easy.

This night I did all of those things. Congratulating myself on having skirted disaster and found safe harbor, I look around. And then I look again because some boats nearby are moving. They are moving forward relative to the background of shore lights.

This can only mean one thing. It means that I am moving backward. I’m dragging the anchor.

What? Now? This? This business of anchoring is exasperating at times.

Or dangerous. The wind is beginning to take me down the anchorage at an alarming rate. Going forward, I can’t pull the chain back. Although the anchor is dragging, it’s still solidly in front of me. I have to motor-up on it to make some slack. Next go forward and pull chain until it pulls back away from me. Snub the chain and return to the tiller. Repeat until the anchor is up.

I’m tired. Your IQ when you are tired drops radically. It’s pretty much equivalent to being drunk. I over compensate. I put the chain under the boat. It catches somehow underneath. I have to motor a circle to release it. Released, I’m halfway down the anchorage and bearing down on another boat.

I sound my air horn to alert any occupants of the boat. It’s a shapely ketch. My greatest fear is that I’m going to drag my anchor over theirs. We get tangled or I simply trip theirs into dragging as well. It seems prudent to warn them. It turns out that the boat is unoccupied, unkempt, maybe abandoned. This turns out because I get near enough to have a very good look.

The ketch turns out to be my savior because, being near it for reference, I can see exactly how far I’ve motored up against my chain. I get a couple of good cycles of motoring-up to get slack and then pulling in chain. Then I find that I can keep pulling, pulling hard, and get the chain up without putting slack on it. The anchor comes up to the surface in my headlamp and it’s celebration time. The little things, we celebrate. I’m free of danger to motor back upwind and try again.

The anchor was no longer an anchor. It was a ball. The anchor had clogged completely with sticky, sandy clay and grass. Grass is the toughest because it resists penetration of the blade of the anchor. In the end, I had nothing more than a dumbbell weight at the end of my chain.

Otto in charge, taking us upwind, I went forward and cleaned-off the anchor with the boat hook. Dropping the anchor again, I put my headlamp on bright and looked into the water before letting loose. In twelve feet of water here, they say, you’ll see bottom. I don’t know, but I see light, like sand, not dark, like grass. Long story short, it didn’t take a third try nor repeat tour downwind.

At three in the morning the day after arriving at Cozumel, sixteen hours after arriving at my point of intended landfall, I was anchored at Isla Mujeres. What the devil had I done? Here it is, recorded, my insanity. One thing leads to another. Sometimes it gets worse and worse before it gets better. It always ends and sometimes it ends in disaster. This we try to avoid.

This time, I’m safe and sound. All I have left to be arrived in Mexico is to pay an agent to authorize me with the authorities and to pay the fees for sailing my luxury yacht in Mexican waters. Here I am, Mexico. Time for that taco I’ve been craving. May it not disappoint.