C to Ruby

This is the fifth in a series of posts about the development of socelect.org. Find the first here, introducing socelect.

Having a C implementation of Davenport’s algorithm, the next step was to make it usable from Ruby. Recall that socelect.org is served-up using Ruby on Rails.

This is the part of the project that I’m finding the most difficult to write about. It was the part that gave me the most trouble. Not so much in the coding, which was a comfortable technical challenge, but with the integration, which gave me the worst nightmare. More about that later.

Ruby C Extension

The Ruby C extension creates, in C, a module that can be included and some functions that can be called in Ruby code.

The most helpful documentation I found about how to do this is

the extension.rdoc in Ruby itself about creating extension

libraries.

We’re essentially programming Ruby with C, using C functions to manipulate C data structures set-up by Ruby. It doesn’t make sense to do anything too complicated or navigate Ruby data structures too much. Those make more sense in Ruby to begin with. Keep it as simple as possible.

There are multiple aspects to a Ruby C extension, which I placed in one file, davenport_ruby.c:

- C functions that implement the methods using

VALUEstructs that represent data parameters passed to them by Ruby, and returning oneVALUE. - C functions and data structures that inform the Ruby runtime how to initialize and manage memory for the extension.

- A C function that defines the Ruby module, class, and methods of the class.

Ruby will invoke this function when it encounters the statement,

require 'davenport'.

To keep things simple, I defined one class, PreferenceGraph that provides

three methods. The methods are:

initialize(called by the class constructor), which allocates a graph with a given number of alternatives (nodes).add_preference, which accepts an array of integer rank numbers, checks that the length equals the number of alternatives given the initializer, initializes a C array from the Ruby array, and invokes thepreference_graph_add_preferencefunction from the Davenport library.davenport, which invokes the Davenport algorithm on the preference graph and returns a Ruby array of rank numbers.

Parts of the code in the latter two functions translates between Ruby arrays and C arrays. The other parts are straight C usage of the Davenport library.

Exceptions

I wanted an exception to throw if the array given to add_preference isn’t

the right size, or doesn’t contain only integers (Ruby Numeric type T_FIXNUM).

At first I thought, “Gee, now I have to define a Ruby Exception class

in C.” Pretty soon it occurred to me to simply define it in Ruby, within the

gem, and use it.

Strangely, in order to access the exception class within the C code, you

call a method called rb_define_class_under. That method has smarts to

return the existing class if it already exists.

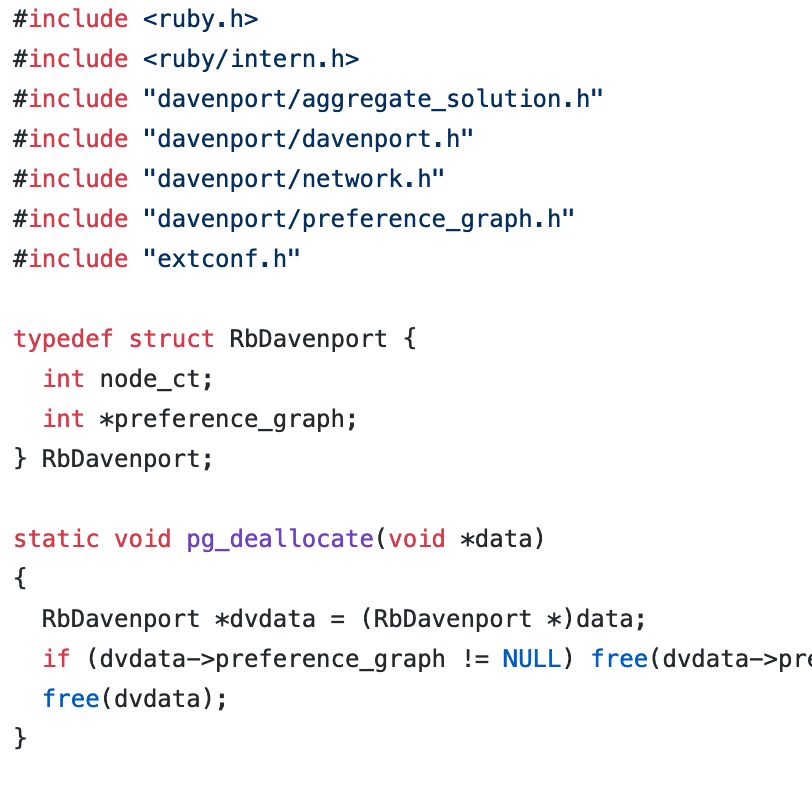

Allocation

The davenport_ruby C extension allocates a data structure that will

represent an instance of the PreferenceGraph class

by defining a function, pg_allocate provided in a call to

rb_define_alloc_func. The function

returns data storage reserved with malloc, initialized, and wrapped up using

the TypedData_Wrap_Struct macro.

That macro accepts a structure, rb_davenport_type that contains

information for the Ruby garbage collector. The information includes

a reference to a method pg_report_size that returns

the amount of data the instance has allocated and a reference to

a method pg_deallocate defined to free it.

The functions implementing the methods of the class access the instance data

for the class using a macro, TypedData_Get_Struct.

Packaging as a Gem

Building and packaging the extension is accomplished through

an extconf.rb Ruby program containing calls to methods made available by

requiring mkmf. The most helpful documents are the

extensions guide

at RubyGems.org and the

MakeMakefile doc

for the mkmf library at Ruby-lang.org.

The gem specification, davenport.gemspec contains a line,

s.extensions << 'ext/davenport_ruby/extconf.rb'

that tells RubyGems to run that file and execute the resulting Makefile using

make. The extconf.rb program uses mkmf methods that check for the

Davenport library and generate the configuration to link it, a C language

header, and a make file specific to the platform.

To enable compilation, the gem requires rake-compiler as a dependency,

and includes a call to Rake::ExtensionTask.new "davenport_ruby"

within a file called, Rakefile within the project.

There’s a “smoke test” Ruby program for verifying that the gem will install properly and function. You can find it as wbreeze/dvt.

An Integration Nightmare

I don’t even want to write about this. It took me three weeks to get over it. When it came to deploying the web site with the Davenport Ruby gem integrated, the site would not operate with the gem. It worked on my development box. It wouldn’t work on the server, which has a different operating system.

Attempting to run the program on the server yielded:

libdavenport.so.0: cannot open shared object file: No such file or\

directory - /home/deploy/.rbenv/versions/2.6.3/lib/ruby/gems/2.6.0\

/gems/davenport-1.0.2.pre/lib/davenport_ruby/davenport_ruby.so\

(LoadError)

The worst part is that there are three different systems where the the problem might lie:

- The coding and packaging of the Ruby C extension gem

- The coding, compilation, and installation of the C library

- The coding and usage within the Ruby program

Each of these (least of all the last, mostly the first two) have any number of details that might be wrong. If you followed the earlier sections of this post, you have an idea of the details involved.

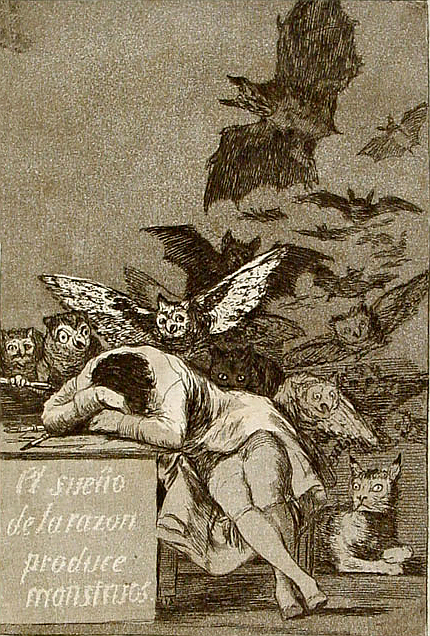

These kinds of problems always give me the jeebies because they aren’t coding problems. They’re devops problems, configuration problems. Many of the same problem solving skills apply; but, I always feel like I’m dealing with a dark, obscure, illogical labyrinth. As with anything, it’s something that can be learned. There are many approaches that can be employed, that shed light into the dark corners and reveal what is going on. Because I don’t like it, I resist it. Overcoming that is maybe more than half the battle.

To make matters more difficult, it wasn’t something that cropped-up on my development OS. It was something that only manifested itself on a remote server running a different OS, or on the virtual server I ended-up installing in order to test.

As the illustration by Francisco Goya implies, we conquer these monsters through reason.

In the end, the message itself needed close examination. All of the other aspects of setting-up the Gem and the C library were correct, although I felt uneasy about them. Doing some good searches using the error message revealed the answer. Searching the error message is always a good strategy. I was too wrapped-up in uncertainty about the whole setup.

The ugly details are in a

StackOverflow question

that I opened seeking help.

It required use of some Linux, shared library diagnostic and configuration

tools, ldd and ldconfig, that were new to me. Posting the query,

following-through the suggestions I received, and reading about linking and

shared libraries were key to breaking-through. The act of describing the

problem in writing is helpful in and of itself.

In short, it was an installation problem with the Davenport C library.

There is a known shortcoming in the autoconf and automake compiling

and linking setup, such that it doesn’t detect the need, on some systems,

to run the ldconfig command after installing the library.

That shortcoming was listed as an implementation

issue

in the GNU documentation for libtool. It’s an opportunity for someone

to make an improvement, probably, to autoconf. I solved it by running

the command after installation and documenting the

need.

Next up

I developed the davenport-ruby gem during the third week of May. (The installation headache came much later, at the end of July.) Find the source on GitHub as wbreeze/davenport-ruby. The next step was to use it. I was ready to start working with the socelect Ruby on Rails code base.